Summoning the Imagination in Games

Posted by Rampant Coyote on September 15, 2015

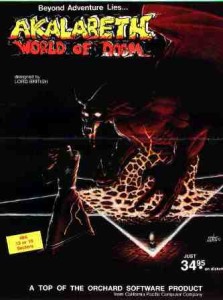

A friend of mine in Junior High School showed me an ad in his computer magazine for Akalabeth: World of Doom. It pictured some kind of wizard near a glowing pentagram with a demon or lava-creature rising out of the earth at the center.

A friend of mine in Junior High School showed me an ad in his computer magazine for Akalabeth: World of Doom. It pictured some kind of wizard near a glowing pentagram with a demon or lava-creature rising out of the earth at the center.

By the standards of the time, it was a pretty cool image. I instantly wanted the game, but it was an Apple II exclusive and I couldn’t have afforded it even if I had an Apple II. Not that I really wanted a game where you summon demons (or have demon summoning go awry) or anything like that, but the image suggested fantasy drama and detail that I really wanted to see. There was a story there behind that image, and I wanted to know what the story was. Who was that sorcerer? Why was he trying to summon such a horrible demon? Why was the world doomed? Or was it just filled with doom?

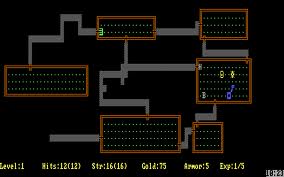

I never did get to play the game… at least not until decades later (thank you, GOG.COM) Sadly, the actual game had zero to do with the ad, as far as I could tell. Mainly the game was wandering around the world starving to death doing assassination missions for the king with clunky line graphics.

It was simply an inspiring ad. I got to imagine all kinds of amazing things in the game. The words “Beyond Adventure” channeled up thoughts of the two text-based adventure games I was familiar with at the time (Zork and Colossal Cave), and of course there was plenty of room for deep, dramatic, detailed stories in that medium. With no screenshots, I could only imagine the kind of awesome game my friends with Apple II’s had access to, even recognizing some of the technological limitations of the era.

Many years later, designer Richard Garriott made follow-ups with far greater depth, story, interesting characters, and worlds facing certain doom. There was even summoning of nasty beings, too. Sorta like he was trying to live up to that old ad.

Many years later, designer Richard Garriott made follow-ups with far greater depth, story, interesting characters, and worlds facing certain doom. There was even summoning of nasty beings, too. Sorta like he was trying to live up to that old ad.

As amazing as the Ultima games were, I think my imagination was a little better. Mostly.

Okay, the destroying of the Black Gate at the end of Ultima 7 was something of a riff on this theme, and it was pretty dang epic for its time, I’ve gotta admit.

I think some of the nostalgia older gamers feel for the classic games comes not from a belief that the games were literally superior to modern counterparts (although sometimes that’s the case), but more in that the older games – out of necessity – did a better job of invoking the imagination. The graphics were clunky, the text was limited, the UI was painful… but somehow we were more involved and engaged, and the world was more real to us than the most amazing graphical available today.

Scott McCloud explains this phenomenon in the book Understanding Comics. The more abstract images invite us to project our own thoughts and ideas into the scene. In some ways, this makes for a far more powerful message, simply because we have invested meaning into it ourselves.

I was reminded of this recently when I read Dungeon Hacks:

To their astonishment, the imaginations of the players filled in the blanks left by inadequate technology. “People would invent meaning,” Toy remembered. “They would place themselves in this situation and their creativity would express itself. They made the world more interesting and beautiful. So even though the thing I created wasn’t beautiful, people would color it with their own imagination, the same way you do when playing a text adventure. I’d listen to someone trying to explain how to play the game to someone else, and they’d start talking about something that was completely ridiculous and made up. They’d say, ‘this is how this particular monster thinks.’ And I’m thinking, That monster? He’s one of the non-thinking monsters!”

Not that I’m a big proponent of going back to ASCII graphics, mind you. After all, this post started with me talking about what I thought was a really cool picture when I was 12 or 13 years old. Although I did get pulled into Moria in a similar way once upon a time. But really, it’s about the world’s presentation being inviting enough to pull a player in (which varies wildly from player to player), and also inviting the player to expand on their own imaginary model of the world.

Not that I’m a big proponent of going back to ASCII graphics, mind you. After all, this post started with me talking about what I thought was a really cool picture when I was 12 or 13 years old. Although I did get pulled into Moria in a similar way once upon a time. But really, it’s about the world’s presentation being inviting enough to pull a player in (which varies wildly from player to player), and also inviting the player to expand on their own imaginary model of the world.

Here’s another excerpt from the book:

“We got drawn into the world, and you would imagine yourself in the world. You’d see a letter ‘T’ on the screen, and it would startle you because you knew it was a troll.”

Nowadays, the focus is heavily on more realistic graphics, and cut-scenes to force the player’s attention on heavily scripted sequences. Is this an artifact of a bygone era, or is it still possible that abstract graphics have the power to cause this emotional reaction in modern players?

For that, I have this answer:

All Minecraft players know, hate, and love the Creeper. He’s become the mascot for the game. And while I’ve seen attempts to render it more realistically, they’ve always failed to improve on this simple, blocky, texelated model. He’s scarier when the details are left to the imagination.

It’s a fine line. On the one hand, I love the exciting modern detail. But artistically, I’d like to leave more room for the imagination to fill in the details. As an indie, I have to do that… I don’t have the budget to provide photorealistic detail for the entire world.

But even more realistic graphics can benefit from invoking more of the imagination. Sounds, reactions, clues about what’s happening in the back-story, explosions caused by something off-screen, that kind of thing.

Interestingly, for me, it feels like the more simulation-driven the game, the more I feel like my mind fills in the blanks. I’d expect that to be more of the case in a story-driven game, but that’s not usually the case. It’s like I assume that it’s not on the stage, it doesn’t exist in a story-driven game. I know that monsters will wait for me, that conversations hadn’t started until I came within earshot, and so forth. With a more simulation-oriented game, I assume the world is always running even when I’m not around. At least on a simplified level, stuff has been happening without me, and that’s where my mind starts filling in conspiracies and attributing design to what could just be coincidence.

Interestingly, for me, it feels like the more simulation-driven the game, the more I feel like my mind fills in the blanks. I’d expect that to be more of the case in a story-driven game, but that’s not usually the case. It’s like I assume that it’s not on the stage, it doesn’t exist in a story-driven game. I know that monsters will wait for me, that conversations hadn’t started until I came within earshot, and so forth. With a more simulation-oriented game, I assume the world is always running even when I’m not around. At least on a simplified level, stuff has been happening without me, and that’s where my mind starts filling in conspiracies and attributing design to what could just be coincidence.

Horror games have really improved over the last several years, showing that the simulation aspect isn’t essential. But the feeling of being “on rails” in some of these titles does lessen the impact, because I feel like everything is scripted and artificial. But regardless, the emotion of fear really does heighten the imagination. It’s a self-preservation instinct. Filmmakers learned a long time ago, they could both reduce the budget and heighten audience tension by leaving some things unseen. Sometimes a glimpse is far more effective than a close-up.

Whatever the case, I feel like mainstream games have gained larger audiences by lessening the imagination requirement. Some folks (including me) prefer more than just the letter “T.” But even in a world where incredible vistas and detailed 3D monsters are possible, games should do more encourage the player to invest their own imagination into the world. Provide enough to kickstart the imagination, and as a player, I’ll happily provide the rest. My imagination still beats VR headgear or a 4K screen, so you want as much of the game playing there as possible.

Filed Under: Design - Comments: Read the First Comment

9/15/15 – Imagination, Emergence, Sectioning, Memorability, and Swords! | Game Design Digest said,

[…] Summoning the Imagination in Games […]