[Archive] Wizardry – The Most Influential Game I Never Played

Posted by Rampant Coyote on June 22, 2015

This is an archived post from 2009, with a few modern edits. To this day, I’ve still never played Wizardry 1 to completion – although I’ve delved a little deeper than I had at the time I wrote this. Still, the post isn’t really about Wizardry. It’s about another game that only existed in my mind.

The original Wizardry (full title: “Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord“) was published in 1981 for the Apple II, written by Andrew C. Greenberg and Robert Woodhead. It was definitely one of the most influential computer RPGs of all time, and it was certainly a big influence upon me. And yet, I never played it.

The original Wizardry (full title: “Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord“) was published in 1981 for the Apple II, written by Andrew C. Greenberg and Robert Woodhead. It was definitely one of the most influential computer RPGs of all time, and it was certainly a big influence upon me. And yet, I never played it.

Okay, “never” isn’t entirely true. But I didn’t have a machine that would even run it for many years. I played it a little on friends’ computers when I could – particularly the gimped IBM port on my buddy’s IBM Peanut – but I never made it past the third level.

But I read about. Oh, did I read about it. It was the single game I wanted most to be ported to my platform of choice during the mid-80’s (by the time it was finally ported to the Commodore 64 – in 1987 according to MobyGames- I had moved on). I read about it and its sequels in magazines. I talked to friends who played it.

In 1983 I bought a book entitled “The Survival Kit for Apple Computer Games,” which I still somehow have in my library. Not that I had an Apple. But back then, books on computer games were still pretty rare. And there was almost nothing for the C-64 out yet, though I knew many developers were frantically attempting to port their libraries to this new system. So I picked up the book in anticipation of seeing some Apple II classics hitting my beloved machine. I was especially interested in the Adventure games and RPGs (which they called “fantasy games” in the book).

In 1983 I bought a book entitled “The Survival Kit for Apple Computer Games,” which I still somehow have in my library. Not that I had an Apple. But back then, books on computer games were still pretty rare. And there was almost nothing for the C-64 out yet, though I knew many developers were frantically attempting to port their libraries to this new system. So I picked up the book in anticipation of seeing some Apple II classics hitting my beloved machine. I was especially interested in the Adventure games and RPGs (which they called “fantasy games” in the book).

I read and re-read the chapter on Wizardry. This was the game… the Cadillac of RPGs. Later, it would be dethroned by Ultima III: Exodus, which enjoyed a much speedier port to the C-64 and would totally blow my mind.

The cool thing about the book is that authors Ray Spangenburg and Diane Moser would not only include some hints and tips for playing the game, but would offer some prosaic paragraphs highlighting interesting or key locations in each game. In so doing, they would inject a little bit of their own imagination into what was otherwise pretty rudimentary, workmanlike in-game descriptions.

Between this book and tons of other reviews and descriptions of the game from other sources, I envisioned Wizardry as a glorious masterpiece of programming and game design virtuosity. Sure, I understood its limitations as a self-taught programmer, and I expected nothing that was technically unfeasible or outside the obvious bounds of the design. But I did envision a narrative thread and event-handling that was far more detailed and complex than really existed. But the Wizardry in my imagination was probably closer to what was eventually realized in SSI’s “Gold Box” D&D games (with a touch of Zork) than what players were enjoying in 1981.

But that imaginary Wizardry became my goal as I continued to improve my coding chops and trying to envision where computer RPGs would be in coming years. I was tilting at a pretty awesome windmill.

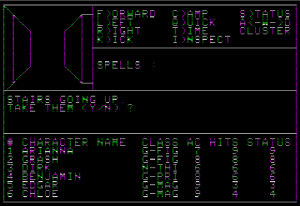

I ended up with one “playable” game that in a proud creator’s blinded vision might vaguely resemble Wizardry. It was a party-based game. It allowed you to create characters,which meant accepting random stat rolls, picking a class, and giving the stat-block a name. You’d travel through a randomly generated maze in search of an “orb” – a very original goal I came up with all by myself. The upper-left corner would display basically one room’s worth of walls and doors, and you could turn and move in pseudo-3D. I had maybe a dozen different monsters that would attack, with a little six-note musical fanfare that would play when combat began and ended. I started out by making the dungeon ten levels deep (with 10 x 10 rooms), but ran into memory issues and had to scale it back down to six. I don’t believe the goal of the game – the “orb” – was ever actually possible to find, but some friends and I had some fun playing my little game together one weekend.

Later, I taught myself assembly language and wrote a routine to display a more complex bitmapped world several squares deep, similar to what you’d see in The Bard’s Tale or the SSI Gold Box Games. It was a simple painter’s algorithm thing that could display fountains and trees and stuff in addition to walls, floors, and doors. I failed to think far enough to realize I could render the whole scene in an off-screen buffer FIRST and then copy to the screen – so as you walked you could catch a split-second glimpse of whatever was behind the nearest walls. That project was never more than a tech demo, though. But hey – the visual display was cooler than that of Wizardry!

But it was the design possibilities that really got me thinking. I’m all about exploration in RPGs. And I struggled not only with the technical issues involved in scripting a world big enough for my imagination, but also just coming up with a world as full and exploration-friendly as I wanted. I wanted a world with all kinds of meaning and story.

I’m still tilting at that particular windmill.

(Editorial Note from 2015: And I feel pretty proud of what I accomplished from that tilting, with the Frayed Knights series…)

Filed Under: Archive, Retro - Comments: 2 Comments to Read

McTeddy said,

Haha, this is something I know well and I’m amazed I wasn’t the only one.

As a kid we didn’t have money for new games. So, my parents would buy me Nintendo Power magazines. I’d study the gameplay, use the maps to play in my head and then I’d design my own games based on the imagined game. Eventually, I learned to program and made games from it.

As I got older I spent games and played… well… everything, but that start is why I’m the designer I am.

Rampant Coyote said,

Okay, so there were at least two of us. Probably more. 🙂

This held true even later. I remember reading several hints and reviews in CGW by Scorpia and others, and since I couldn’t afford the games, trying to imagine what they were like.

I won’t say that the games were always a disappointment when I finally played them … after all, if I *really* had high expectations, I would have found a way to buy them. But a lot of the features that were supposed to be really, really cool turned out to be a lot less interesting once you tried them out. I guess imagination was still required.