RPG Pacing

Posted by Rampant Coyote on November 28, 2014

I should keep a collection of weird (but sometimes insightful) ideas that I get when I’m busy working on my game after midnight. It seems that the combo of fatigue and focus in the late hours on the nuts and bolts of RPG development cause some strange “thinky thoughts” (as my wife sometimes calls it). If nothing else, they are blogfodder.

I’m constantly contrasting the concepts in “modern RPGs” (think Bioware) with older, classic RPGs (pre-1996, let’s say). I do that a lot on this blog. That really isn’t intended to say “older is universally better.” Maybe some really hard-core fans of the classic CRPG era say that, but I remember complaining about some of the problems with CRPGs to friends back in the early 1990s, and applauded the changes and pushes that came since. I just didn’t know they were going to go so far – or that elements that I really did enjoy (or enjoyed in moderation) of these older, classic RPGs were going to get all but eliminated from the genre until the indie era resurrected them.

That’s really what I’m about – not a complete rejection of the new in favor of the old, but being willing to question the modern “evolution” and explore some babies that might have been thrown out with the bathwater in the never-ending quest for the ill-defined, shifting and ever larger mass market.

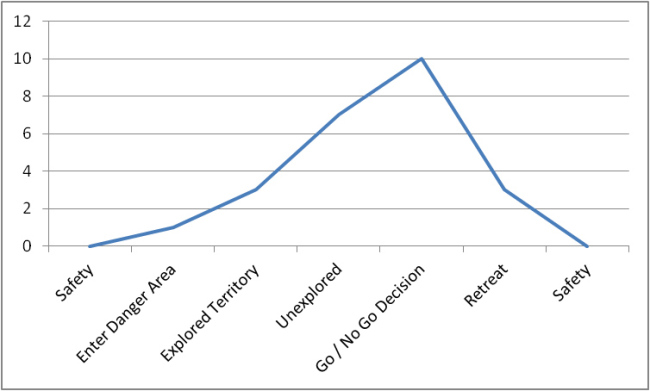

One aspect I was pondering in kind of the “too-tired to think about this” way was RPG pacing. In the old days – I guess I could say, “There was no such thing,” but really, it was completely in the player’s hands. It depends upon the game, but following the tabletop D&D model, the gameplay consisted of a number of player-directed pushes into dangerous territory. Maybe it was exploration from a home city out into the wilderness, or from the Edge of Town into the deep dungeon, or whatever, but the player drove their own pacing. The rise in tension depended on player choice, but it looked something like this:

Those are dumb names at the bottom, but on a scale from 0-10 of tension (I’m a programmer, we start counting at 0), you have the stages of “delving deeper”. First they are in a place of relative safety – no tension. This is important. Just as Shakespeare wrote comic relief into his tragedies, people need a chance to re-center their emotional levels. The tension can’t keep rising forever or it just tops out for a while, and then causes fatigue, and will actually drop after a while. That’s a problem in some horror games, I’ve noticed.

After that, the player chooses to leave the area of safety to a “danger area” – like a dungeon, or the wilderness. At the beginning of the game, this may be a high-threat area – they don’t go too far before they have to retreat back to safety. Later, this area presents little threat beyond the use of resources, and it’s more of a case of trying to be efficient than being in mortal danger. That first step represents some small amount of tension, but you are rarely attacked immediately as you step outside the front gate. But the deeper you go, the further you are from safety, and even areas of low to moderate threat – like previously explored areas of a dungeon – represent a rising danger and tension level. Then you get to the new, scary, fun, exciting areas. This represents a serious threat (and serious fun), as you may not know what to expect, and may be facing unfamiliar threats (new monsters, etc.).

At some point – possibly as you are about to face the “level boss” or just find yourself barely surviving some encounters – you have to make a go / no-go decision. At some point, you realize the threat is too great, and you are either already or about to get into some serious trouble, and you have to retreat back to at least relative safety. In classic RPGs, this was maybe unsatisfying from a storytelling standpoint (you defeat the uber end-level boss only to have to keep fighting his minions on the way to the exit), and frustrating when you failed, but it was still an exciting part of the story. This was in some ways a “chase scene” – you were out of resources and unable to sustain many (or any) serious fights. Maybe even what was only a moderate threat on your way in represents a serious threat in your weakened condition on the way out. However, the closer you got to safety, the less tension there was. Finally you made it home (not necessarily the same “home” you left) safe, rested and resupplied, and the tension began again. This might represent a really good save point (in a few games, it was the only “save point”).

There is an interesting point worth mentioning here.Modern games have significantly reduced the concept of long-term resources in RPGs. In the older games, the push through explored territories (and possible encounters) was pretty much low-quality content and a “tax” on the previous decision to retreat, a constant depletion of resources that represents the strength of the party. It also means that, except for newly-discovered equipment / supplies found on the way or level-up events that occurred during the excursion, the party is never stronger than the moment they leave their safety area, and they are never weaker than the moment they re-enter. So it’s not that the tension rises necessarily because the players’ obstacles grow in threat, but because the players are (temporarily) depleted. It’s admittedly not as great from a storytelling perspective that a party that just mopped the floor with fifty minions and their boss overlord are now forced to flee from a small group of minions because they’ve used up all their resources (think “ammo and supplies”), but it works just fine as a game mechanic.

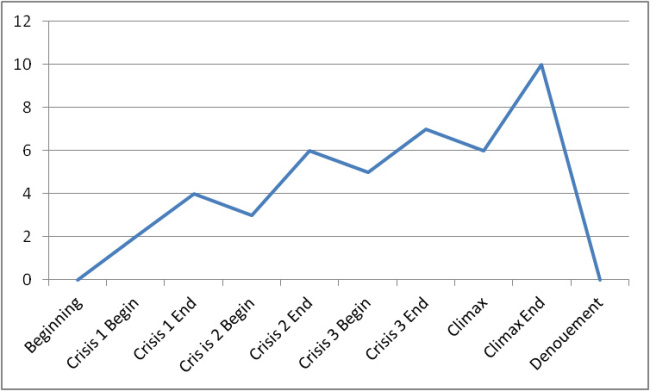

While modern games often give you the opportunity to cancel the curve early to return and resupply (or just sell stuff), the tension curve is more narrative-driven (or, if you will, designer-driven). You enter a section of the story (subquest, whatever), and it’s intended to play to completion along the standard dramatic structure from start to finish. Many modern RPGs more-or-less force you into this structure, with no real way to return to safety except to go through the other side. That can be an exciting change of pace, but it can get pretty exhausting if used exclusively. There’s nothing inherently wrong with this traditional dramatic template. It’s a classic structure that obviously appeals to gamers as well as readers. It allows designers to craft a story. Kind of.

While modern games often give you the opportunity to cancel the curve early to return and resupply (or just sell stuff), the tension curve is more narrative-driven (or, if you will, designer-driven). You enter a section of the story (subquest, whatever), and it’s intended to play to completion along the standard dramatic structure from start to finish. Many modern RPGs more-or-less force you into this structure, with no real way to return to safety except to go through the other side. That can be an exciting change of pace, but it can get pretty exhausting if used exclusively. There’s nothing inherently wrong with this traditional dramatic template. It’s a classic structure that obviously appeals to gamers as well as readers. It allows designers to craft a story. Kind of.

The downside is that a game isn’t a passive medium, and one size doesn’t fit all. When you are an active participant rather than a passive audience, you deal with the tension differently. And then you’ve got this awesome ability of games to be interactive and to tailor themselves to the player’s individual preferences, but instead they are getting pushed through at what the designers and testers thought was appropriate pacing.

For me, personally, I’d like to see things a little more mixed. I don’t just mean giving the player the ability to bail and come back in a more plot-driven structure, and I don’t just mean alternating between the two styles, either. I am certain it’s been explored in many games – maybe not exactly in these terms, but I know pacing and interactivity are a regular point of discussion in design meetings for story-heavy games (at least the good ones). I’m not talking about anything revolutionary here. Just a different way of thinking about it, and a reminder that there really was something to the old-school RPG way of doing things that was both comfortable and compelling.

Filed Under: Design - Comments: 2 Comments to Read

Rasch said,

Great post.

Not really quite sure I get what you mean by the old school approach. Could you give an example? Perhaps compare an old and a new game.

Looking at a relatively modern RPG, Dragon Age Origins, you typically always have the option of leaving a dungeon to go back to restock stuff and heal up (not that you really have to).

Rampant Coyote said,

A canonical example would be the first Wizardry game (although most games fell into that pattern). You make excursions into the dungeon, but there’s no expectation at all that you’ll push through to the end in a single foray. Might & Magic 1 and 2 – which appeared years later – follow a similar format. The older Ultimas, too… you’d start out in or near your “safe” city, but you wouldn’t wander too far into the wilderness (and certainly not into any random dungeons) until you had a level or two under your belt. (And in at least U4, the creatures of the wilderness got more dangerous later in the game, which made things doubly nasty for slow starters).

The big contrast with a game like DA:O is that you really don’t have to – most of your abilities are on a timer, you auto-heal between encounters, and while you may burn through expendable resources, it’s a much slower pace and they are less critical (compared to, say, D&D rules that a lot of older games are based, where even spellcasting is a limited resource).