Appendix N – Breaking the Old-School Fantasy Game Code

Posted by Rampant Coyote on March 14, 2017

For the Frayed Knights games, I really wanted to capture the old-school spirit of not just computer RPGs, but also the style of tabletop D&D games I remember playing and envisioning as a kid. Things were different back then. If you read the old modules (both by TSR and third-party publishers), the original rulebooks from the 1970s and early 1980s, and the articles and letters in early issues of Dragon Magazine, its obvious that there was a different feel to the game back then. Working on Frayed Knights, I tried to get in touch with that feeling.

But I still always felt I was missing something. Now, I think I found it. Amusingly, it comes about because of my rediscovery of classic pulp fiction. I love it when my passions converge!

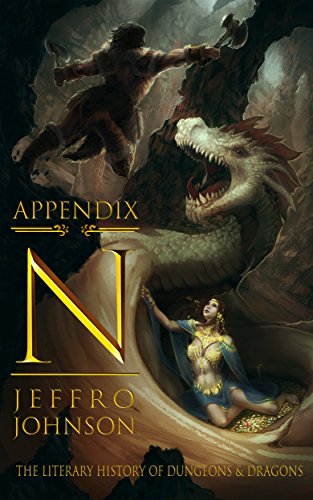

A couple of weeks ago, I read Appendix N – The Literary History of Dungeons & Dragons, by Jeffro Johnson. This book is based on a series of blog posts where he provided a literary critique of the stories that Gary Gygax included in Appendix N of the 1st edition Dungeon Master’s Guide. These were the stories Gygax claimed had the greatest influence on the game.

Gygax wrote, “Upon such a base I built my interest in fantasy, being an avid reader of all science fiction and fantasy literature since 1950. [These] authors were of particular inspiration to me. In some cases I cite specific works, in others, I simply recommend all of their fantasy writing to you. From such sources, as well as any other imaginative writing or screenplay, you will be able to pluck kernels from which will grow the fruits of exciting campaigns. Good reading!”

I read a handful of these as a kid. I was a much bigger fan of Conan and Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser than I was of Aragorn. I loved Andre Norton. While I never read A Face in the Frost, I loved The House with a Clock in Its Walls and the rest of the Lewis Barnavelt series as a kid by John Bellairs. And of course, the Amber series was a must-read for fantasy fans back then. More recently, I’ve been reading the Barsoom and Tarzan stories by Edgar Rice Burroughs, and for the last couple of years I’ve been on a slow-burn binge read of Leigh Brackett’s stories.

Gygax followed up by stating, “The most immediate influences upon AD&D were probably de Camp & Pratt, R. E. Howard, Fritz Leiber, Jack Vance, H. P. Lovecraft, and A. Merritt; but all of the above authors, as well as many not listed, certainly helped to shape the form of the game. For this reason, and for the hours of reading enjoyment, I heartily recommend the works of these fine authors to you.”

As I grew older and became college-age (and pretty much ignored 2nd edition D&D), I bought into the common assumption that Lord of the Rings was by far the largest inspiration for Dungeons & Dragons (outside of real-world mythology), and that Gygax cited the longer list as a butt-covering move due to TSR’s legal clashes with the Tolkien estate. Now, after reading Jeffro’s surprisingly detailed and extensive book, I’m pretty convinced otherwise. I think Gygax was being sincere. I knew of the Vance connection (especially when people describe D&D’s unique and much complained-about magic system as being “Vancian.”), but even as a fan of Lieber, Howard, and Lovecraft, I wasn’t really sure how big of an influence they really were. Jeffro goes well beyond literary criticism, and really demonstrates how he believes these stories impacted the game, it’s style, and how some of the apparently stranger or more confusing design decisions may have been an attempt to accommodate these kinds of stories into the game.

It’s an eye-opener. A lot of talk lately has been about how people have suddenly rediscovered pulp because of his book (or the original blog posts), which is something I’ll talk about later this week. But from a game-design perspective, as a guy trying to infuse a game with that old-school flavor that I feel has been lost over the years, this has been a gold mine. It explains so much, and I think it’s helped me “crack the code” and understand the source of some of this “old-school feel” I’ve struggled to define – drawing inspiration from the same sources.

It’s an eye-opener. A lot of talk lately has been about how people have suddenly rediscovered pulp because of his book (or the original blog posts), which is something I’ll talk about later this week. But from a game-design perspective, as a guy trying to infuse a game with that old-school flavor that I feel has been lost over the years, this has been a gold mine. It explains so much, and I think it’s helped me “crack the code” and understand the source of some of this “old-school feel” I’ve struggled to define – drawing inspiration from the same sources.

In some ways, it makes me feel like fantasy RPGs have become too hidebound. I know that’s not really the case, and that designers at the very least have tried to push the boundaries and do things that went beyond Tolkienesque elves and pseudomedieval Europe. But those are a hard sell. Players (myself included) are pretty grounded in a generation of fantasy literature that consisted primarily of Tolkien and books that wanted to be like Tolkien that came out of the 1980s and 90s. I think we’re coming out of that nowadays, but its a slow drift as readers seek “something different” not realizing just how different things were before Tolkien was retroactively discovered. That legacy remains, codified in later editions of D&D and in generations of players. It’s like we’re playing a copy of a copy. (Ummm… Analog copies, for younger readers, suffer from inevitable degradation from the original source… and a second-generation copy was often of pretty poor quality).

For some concrete examples cited in the book: The fantasy source material was a lot more fast and loose with the boundaries between genres. In part, because there were no boundaries when some of these stories were written… genres were created as marketing distinctions. A lot of the fantasy back then wasn’t “second world fantasy,” but took place in our own world, with explanations of how the history become lost in the mists of legend. A lot of the fantasy stories cited were actually post-apocalyptic stories of a future Earth after technology has been lost… again, a blending of subgenres. The roles of the paladin and the thief were pulled a bit from certain pulp fiction stories, and the concept of alignment was a lot more concrete in a couple of these books.

For some concrete examples cited in the book: The fantasy source material was a lot more fast and loose with the boundaries between genres. In part, because there were no boundaries when some of these stories were written… genres were created as marketing distinctions. A lot of the fantasy back then wasn’t “second world fantasy,” but took place in our own world, with explanations of how the history become lost in the mists of legend. A lot of the fantasy stories cited were actually post-apocalyptic stories of a future Earth after technology has been lost… again, a blending of subgenres. The roles of the paladin and the thief were pulled a bit from certain pulp fiction stories, and the concept of alignment was a lot more concrete in a couple of these books.

But some of it is more of a feel and flavor thing, and that may be as much an artifact of the authors as of the era the stories came from. There was more to it than the high-fantasy / low-fantasy divide Brandon Sanderson talks about. But even more of it was simply the breadth of the gaming experience D&D was expected to (imperfectly) fill, which filtered down to the kitchen tables of those of us who never played with designers via rules, adventures, supplements, and articles. Over the years, we narrowed that experience down, and then scratched our heads at why the rules didn’t fit perfectly to our more limited game.

On top of all of this, Jeffro uses these reviews as a springboard for some decent advice for running and playing D&D (or any tabletop RPG). While it seems he intended this to be more of a fifty-fifty discussion about literature and gaming, it does seem the gaming parallels are secondary. Someone who has no interest in role-playing games can find a lot to discover and enjoy here, and in fact most of the discussion about the book lately has nothing to do with gaming at all. But the primary audience originally was gamers, and those who love slinging real or virtual dice and fighting imaginary dragons will benefit from this book the most.

Like I said, I’ll have more to say about this book later, from a more literary perspective. But as I’ve got another dungeon level to work on tonight for FK2, I’m happy to have read this book and gotten more in touch with that elusive style I’ve been trying to recapture. And my “to read” list has expanded considerably. But that’s not a bad thing.

Filed Under: Books, Design, Impressions - Comments: 7 Comments to Read

Modran said,

Conan was until recently proeminently displayed in my library ! I’ve tried Leiber, but didn’t reall warm up to them characters. I suspect the translation didn’t help. But, as I discovered them later than others, I remember thinking there was somthing “unifnished”, unpolished about them. As you say, they were building the genre as they went.

There are many names here I don’t recognize… ‘M gonna write them down, you never know.

Rampant Coyote said,

That’s a discussion point right there that I’ve had with friends about older pulp. My contention is that the stories are no better today than they were then. And the less-defined genre boundaries and marketing limitations arguably gave them a lot more leeway, without the fear of getting fantasy in their science fiction, etc.

However, I do argue – and this is the subject of debate – that *storytelling* has improved today over what we had in the pulp era. Now, some friends argue that it’s more of an audience preference thing, and it could be right. But I think that while some areas may be more of a temporary preference thing, some storytelling techniques (like using a more active voice, etc.) have evolved and improved over time. We learned from their experiments.

That may be why the older stuff may seem a bit more raw or unpolished.

Adamantyr said,

If you haven’t yet, read “Face in the Frost”. It’s actually incredibly good and a bit sad, because John Bellairs was told by his agent he should focus on children’s books after writing it and he never returned to attempting adult fantasy.

He did start a sequel to it “The Dolphin Cross” He shared it with a friend who urged him to finish it but he never did. You can read it in the Magic Mirror anthology collection.

Rampant Coyote said,

Well, I *do* appreciate his children’s books. But Face in the Frost is going on my list. 🙂

Adamantyr said,

Oh yes, I love his children’s books as well! I’ve been working at collecting them all from Half-Price and other used bookstores for some time.

I’m also trying to get the Brad Strickland books; he took over the characters and stories (with Bellairs estate’s approval) after Bellairs passed away. He completed several unfinished manuscripts and started doing his own. Most are out of print now and tough to find.

FallenAngel said,

I’ve never really got much of a Tolkien vibe from D&D, even decades ago…but perhaps that’s because I tend to focus on the portrayal of magic in fantasy settings and the differences concerning magic between D&D and Lord of the Rings for example are enormous.

LotR’s magic is mostly item based. Palantiri, rings of power, all of the magic swords and so on.

There aren’t really any mages running around studying their craft in academies or the like.

There’s the wizards of course, but those aren’t mortals but Maiar spirits in human form and thus don’t really count and even then…the magic of even highly powerful beings like Gandalf isn’t remotely as showy as the spells D&D mages usually cast, but often(though not always) more subtle like duels of will, ESP, ambient effects or nature control.

Contrast with D&D mages flying through the air throwing fireballs and lightning bolts while protected by glowing force fields(and that’s at low-ish levels) 4-color superhero style and that’s why, to me, D&D never seemed much like Tolkien(beyond dwarves and elves and halflings which were everywhere anyway).

Rampant Coyote said,

For wizardry, yeah, not so much. Of course, when players complained about magic-users not being able to use a sword, their go-to example was Gandalf. Not that they were willing to accept Gandalf’s low-key approach to magic.