A Bit of Navel Gazing for the New Year

Posted by Rampant Coyote on January 1, 2015

I don’t feel like commenting much on 2014. Not that it was bad. Like all years, it was a mix. It had some pretty awesome milestones – from seeing a short story published in a book for the first time, to getting Frayed Knights: The Skull of S’makh-Daon on Steam, to running a kiosk at Comic Con, to seeing my daughter off on her mission for the church in South Carolina, to performing vintage dancing at a public event, to getting a new puppy, to going to Japan for the first (maybe only?) time.

Okay, you know, on the whole, I think it was a pretty awesome year.

My one big regret is an obvious one… Frayed Knights 2 didn’t ship. I knew it wouldn’t by last summer — it was nowhere close, although the big push for Comic Con really helped. Actually, it helped in a lot of surprising ways, not just in getting stuff done and back on track, if slower than expected. We’ve made a lot of changes (for the better, IMO), but the big push also revealed some things that have been really slowing us down and impacting the quality of the game. It caused some major redesign and clean-up … and watching strangers play the game triggered yet more improvements. And… compromises. I know that sounds like an ugly word, but I have had to make some hard decisions just in order to get the game back on track. And… to be honest, while they seemed hard at the time, in retrospect they still feel like the right decision.So, here’s hoping 2015 is an even better year for us all! Good times!

Filed Under: Rampant Games - Comments: 7 Comments to Read

Happy New Year!

Posted by Rampant Coyote on December 31, 2014

Happy New Year, everybody! I hope 2015 brings you a good deal of real-world joy and success, and virtual-world fun.

Be excellent to each other, and party on dudes and dudettes!

Filed Under: General - Comments: 3 Comments to Read

Dating Sim + Horror

Posted by Rampant Coyote on December 30, 2014

I can’t say I’m a connoisseur of Dating Sims, but the ones I have played felt like a very interesting and different subspecies of RPG. If you haven’t played one – it’s a specially focused implementation of a “Life Sim.” If you haven’t played one of those … well, you know what “The Sims” is? Scale that down to indie size and provide more of a storyline. Long Live the Queen by Hanako Games is an excellent example. Also, pretty much any of the Visual Novels and RPGs by Winter Wolves games include some romance elements that borrow from dating sims.

While I really enjoyed some of the few dating sims I played, there was something that felt kind of creepy about many of them. Basically, you level up your protagonist and perform day-to-day activities earning skills / cash / gifts / whatever to keep going and to impress other characters in the game so that you can date them. Really popular in Japan, they’ve picked up a bit of a casual following in the west as well. But at least for many I have played, there’s something kind of creepy about the mechanical / strategic way in which you play the romance game. Fulfill the correct parameters, answer the questions correctly, and your standing moves up with the character. That’s nothing unusual for romance elements in an RPG, but where it’s the focus of the game…

Like I said, I enjoy it, but there’s something a tad creepy about it.

Mixing this with horror elements isn’t new. I’m not well-versed in the genre, but Winter Wolves’ Nicole is an example of a full-blown indie dating sim with a horror / thriller angle.

There’s a kickstarter campaign currently going on that takes it to a whole new level – as far as I can tell, really taking advantage of the absurdity of some of the plots and mechanics of many of the lower-end dating sims to turn what sounds like a young man’s dream scenario – getting stranded in a community of beautiful young women all interested in you – into a nightmare.

There’s a kickstarter campaign currently going on that takes it to a whole new level – as far as I can tell, really taking advantage of the absurdity of some of the plots and mechanics of many of the lower-end dating sims to turn what sounds like a young man’s dream scenario – getting stranded in a community of beautiful young women all interested in you – into a nightmare.

Kickstarter: “But I Love You” – a Horrific Take on Dating Sims

As described in the campaign, “Once you get in town, the occupants all flock to you, intrigued by the stranded newcomer. At first, they try to help in their own little ways, but as they grow attached, they try to convince you to stay with them. Forever. That’s when you notice things are very, very wrong in this town, from the datable characters to the setting. Once the player starts to notice a trend of the girls starting to be slightly, well, nuts, it becomes a puzzle horror game. The game still features multiple endings like a dating sim, some of them romantic, some where nothing happens, and a few where the player is…dead. You also have the option of ignoring all of the bad stuff and pretending everything is a-ok to keep scoring with the ladies.”

This is not a recommendation. In fact, I have serious concerns about this game ever making it to release (which means I estimate its chances below 80%). It’s being made by an inexperienced developer, which flashes all kinds of warning signs in my head. But I’ve blown $15 in worse ways before, and I love the core idea. It sounds like a great way to make the creepiness work for the game. Perhaps this isn’t the first time this idea has been explored, but it’s new to me.

What I like most of all is the fact that indies are continuing to push genre boundaries – to do unlikely mixing-and-matching and subverting of tropes, and really play with audience expectations to make new experiences. These experiments aren’t always successful (IMO, they fail more often than they succeed), but it needs to happen.

Filed Under: Casual Games, Indie Horror Games - Comments: Comments are off for this article

A New Addition

Posted by Rampant Coyote on December 29, 2014

A little over a year ago, our 15-year-old dog Maya died. She was a rescue – we got her when she was 4 years old, and she came with us through a move and had been there while our two daughters grew up. When she passed away, it was a lot harder on all of us than I’d expected. And that, we thought, was that. We didn’t plan to get a new dog.

But time heals all wounds, I s’pose. And I also s’pose we’re a dog family. We’d started discussing the possibility in the vague future two or three months ago. And then some puppies became available.

This weekend, after returning from a holiday trip to Cedar City, little three-month-old Clara joined our family.

Anyway, she’s half Border Collie, and half Australian Blue Heeler (AKA Australian Cattle Dog). Or, as I like to put it – half Lassie and half Mad Max’s “Dog.”

And yes, according to my wife, her full name is “Clara Oswin Oswald Barnson.” Although I’m beginning to question the wisdom of naming our puppy after the Doctor’s most willful companion to date (if you don’t count River).

Life around the Rampant Coyote household just got a lot busier / crazier. But she’s awesome.

Filed Under: General - Comments: 3 Comments to Read

Game Dev Quote of the Week – Spit-and-Polish Edition

Posted by Rampant Coyote on December 26, 2014

This week’s quote comes from an older post at Gamasutra – “The Art of Polish: Developers Speak.” There’s plenty of good advice there. Including this:

“Polish is often adding things nobody will ever notice, comment on, or appreciate, but will notice, comment on and appreciate when they aren’t there.” – Frank Kowalkowski (of Interplay, Obsidian, and Blizzard).

Kinda like housework – it’s only noticed when it isn’t done (or done right).

The trick, of course, is that it’s never enough. As they say, the perfect is the enemy of the good, and there are always more rough edges, more things that could be fixed or improved, and things that could be overhauled to provide a better experience. This is touched on in the same article, with Duke Nukem Forever cited as an example of falling victim to this endless pursuit of “better.”

This is maybe the flip side of Kowalkowski’s comment. It’s all about what will get noticed if it’s not done. And noticed by whom? Sure, somebody looking for flaws will always be able to find one more. But that’s not the person you need to please.

I can’t say I’m an expert on it – I’m really not – but I think one approach is simply watching (really watching) someone else play your game. When you see the getting hung up on or confused by something, or you feel yourself needing to explain or especially apologize for something – there’s a spot that needs more polish.

Filed Under: Design, Quote of the Week - Comments: Read the First Comment

Merry Christmas!

Posted by Rampant Coyote on December 25, 2014

Merry Christmas all!

I’m off spending time with family, so don’t expect to see me around much. But for a couple of cool Christmas-ish links:

GOG.COM – Free Release: Akalabeth: World of Doom

GOG.COM – Free Release: Akalabeth: World of Doom

John Romero Gets His Own Head on a Stick for Christmas… kinda …

Anyway, I hope you have a very happy day. Be excellent to one another, and have fun!

Filed Under: General - Comments: Read the First Comment

Updated Video Policy

Posted by Rampant Coyote on December 24, 2014

Since I had trouble finding a previous blog post where I granted permission to people to make “Let’s Play” videos, I decided to turn it into a separate, permanent page (which is part of the menu bar at top – “Video Policy”).

It’s not a long policy. The short version is – yes, go ahead and make videos. Feel free to even monetize the videos. I just ask that you please provide attribution and a link back to a legitimate sales page (for example, here, or one of our authorized distributors or affiliates, like Steam or Desura), but as long as you aren’t trying to represent the game content as your own (and what kind of jerk does that?), have fun.

Filed Under: Rampant Games - Comments: Comments are off for this article

The Game Biz is the Same All Over

Posted by Rampant Coyote on December 23, 2014

I am happily back from Japan. I had enough time to wash my clothes and turn in an expense report, and now I’m heading off to Cedar City, Utah to spend Christmas with the in-laws. It is in months like these when my laptop becomes my primary development platform. Le sigh…

But hey, this was my first time to Japan. I got to ride a bullet train past Mt. Fuji. Here’s a snapshot from my window as I rocketed past:

And a little pic of me from the ruins of Yoshida Castle in Toyohashi (I’d heard of neither the castle nor the city until I took this trip, but hey, cool…)

We were partnered up with another company on this project. As I sat inside a little break-room at the training facility eating lunch with the representative from this other company, we got chatting about our careers. And it turns out, he’d previously worked in the video games biz as well. In his case, he’d been a 3D modeler working for Nintendo during the Nintendo 64 years.

We compared notes, and man… tales from the trenches. Different country, different culture, but our stories were remarkably similar. Brutal hours, canceled projects, and the amazingly restrictive technical limitations of the platform, and the clever hacks they did to try and make the best of those limitations. I think he told me they were restricted to 32 x 32 texture sizes, but I think that was only with full-color textures… they had to get creative with two-color textures to help hide the limitations, which may have been able to be at a larger size.

But yeah – the industry had the same chew-em-up-and-spit-em-out mentality in Japan as in the U.S. Are / were European game companies the same? Anyway, it seemed like we enjoyed a moment of camaraderie that came with swapping tales of working in the biz.

I would like to believe that the indie revolution has helped bring a little bit of sanity to the industry in that respect, but I don’t know. Much of that mentality originated back in the old days when things were… well, a lot more indie. When you had a tiny number of people with a serious personal investment in the games (and the chance for big personal rewards on success), they’d be fully motivated to move heaven and earth to build their masterpieces. What happened was that over time, as this mentality flourished, the big companies took over. The personal investment (and personal gain) went away, but the big studios did all they could to keep the mentality alive.

So people (usually “kids” in their 20s who didn’t know any better) were still killing themselves, but this time to make someone else rich.

At least in the indie world, the ownership is (usually) back where it belongs.

Filed Under: Biz, Indie Evangelism, Retro - Comments: 4 Comments to Read

I Can’t Tell Great from Good

Posted by Rampant Coyote on December 22, 2014

I’ve been playing video games for… um, a long time, okay? Seriously, when I was little we had one of those Telstar game consoles with the built-in knobs that had three variations on Pong. So… yeah. Been a while.

And in that time, I have (occasionally) reviewed games, made games, had my games reviewed, and played a lot of games. I think critically about games. I like to believe that I think deeply on games. But I have a confession – perhaps not a new one, as it’s not exactly a new realization, but something I keep getting reminded of as time goes by:

I can’t tell a great game from a good game.

Seriously. I mean, I can generally tell a bad game from a mediocre one. I can maybe tell the difference between mediocre and good. But it gets harder, especially when a game is not consistently bad or consistently competent. I mean, what if a game has poor graphics but good gameplay? Or vice versa? What if it has a lot of great ideas but execution doesn’t meet the ideas’ potential? That’s bad enough.

But aside from clear production value differences (which I feel are artificial and clearly designed to sway people like me who have the same problem), it’s difficult for me to put my finger on what really sets the “great” games apart from their merely “good” counterparts. I can identify some parts that seem brilliant, but whether or not that really sets a game above the others is something I can’t answer.

For me, Super Mario Brothers was a “good” game. It wasn’t really my thing, but I could see how it was well-executed. When my girlfriend introduced me to it and was singing its praises, she was mainly going on about the quality of the graphics. (Yes, how’s that for a switch?) I thought, “cool,” and I enjoyed playing it, but it wasn’t until years later that I discovered how well it had aged, and began to really understand what made it “great.” Likewise the original Legend of Zelda. I had a blast playing it, even though I would have preferred something that was more of a “real” RPG. Super Meat Boy is an indie example where I can recognize the skill that went into the game, and I have to admit that I end up playing way too much of it even though it’s a style of game I don’t usually prefer (which I should probably treat as a clue for future estimations). But I don’t love it.

Likewise, there were a few games I really thought of as impressive that haven’t strongly resonated among gamers the way I’d expect a “great” game to do. Like Vampire the Masquerade: Bloodlines, which has kind of become more of a cult classic, although I recognized at the time that some of its flaws and bugs held it back from true greatness. I’m still a major fan of the indie RPGs Din’s Curse and Knights of the Chalice, which I consider absolutely great games that few people have ever played (and even fewer share my opinion of them).

Not that becoming a mainstream “hit” is required for a game to be considered “great,” but I do end up doubting my tastes sometimes. I know I’m not entirely lined up with the average joe gamer.

So… I guess I’m not destined for a career in games journalism. Or something. Beyond certain clear thresholds of quality, my opinion of a game becomes highly dependent of my own biases and preferences.

But I have a sneaking suspicion I’m not entirely alone in this. Why is there such pressure among game reviewers (or from their editors) to make sure that their reviews don’t deviate too far from the norm established by GameRankings or whatever? Is it because they are not confident of their own ability to determine subtle shades of quality?

That’s why – if I were ever in charge of rating games – I’d like to limit it to three possible ratings: Bad, Okay, and Good. Or, “Hated it”,”Liked it,” and “Loved it.” I just don’t know that I could really nail things down to a greater level of detail than that.

Filed Under: General - Comments: 4 Comments to Read

RPG Design: An Imperfect Union

Posted by Rampant Coyote on December 19, 2014

When this article posts, I should be in the air with most of the Pacific Ocean behind me, on my way back from Japan. Didja miss me? Didja even notice I was gone?

Spending a week and a half in the Land of the Rising Sun kinda made me want to play Persona 3 and Persona 4 again. Maybe it’s all the kids in school uniforms and being able to buy Octopus Jerky. Not that I have actually bought the stuff, mind you… it’s just available. The little Japanese culture references in those games – which probably aren’t even conscious references by the designers – make the games stand out a little in my mind. Dang those were good games.

Spending a week and a half in the Land of the Rising Sun kinda made me want to play Persona 3 and Persona 4 again. Maybe it’s all the kids in school uniforms and being able to buy Octopus Jerky. Not that I have actually bought the stuff, mind you… it’s just available. The little Japanese culture references in those games – which probably aren’t even conscious references by the designers – make the games stand out a little in my mind. Dang those were good games.

I managed to do a little bit of RPG playing during this trip (though it’s been pretty busy…). I had a total party wipeout in Wizardry 6 (since I had only one, you can infer correctly I didn’t play a lot of it), re-explored more of the gigantic basement of Lord British’s castle in Ultima Underworld 2, got cracking with a deadly spoiled brat in Loren the Amazon Princess, and revisited my old standby Din’s Curse for some quick hacking and slashing. I expected to get really serious about Dead State once I get home.

As I’ve been dividing my productive time between fiction writing and game development, I’ve once again been mixing and matching lessons from each creative endeavor. As writing is a far older, more popular, and far more developed field, there is a greater quantity of useful (and useless) information available on the subject. I found myself reading about the development of first chapters of a novel, and immediately considered the applicability in computer role-playing games.

In principle: Lots. In implementation: Iffy.

In the early 90s, there was a pretty clean delineation between “Western” RPGs (wRPGs) and Japanese RPGs (jRPGs). The jRPGs really started taking advantage of solid storytelling technique, and their popularity soared. Meanwhile, for a while, the wRPGs kind of went into a popularity decline, as the storyline of “Hey, dungeon! Beat it!” didn’t compare too well, even though the dungeons were becoming really pretty dang cool and interactive.

We still end to use those distinctions, although the styles of games have probably had more in common for much longer than they were really separate. Unfortunately, some of the wrong lessons were learned (IMO) – both styles of games accrued insufferably long intro sequences before the player is allowed significant interaction (and as much as I praise the Persona games, yeah, they are like that, but hardly the worst offenders), and clicky-actiony interaction masquerading as gameplay (because keeping the player busy leaves them less time to think about how the gameplay sucks, I guess).

It sometimes feels like we kicked the happy medium to the roadside.

Of course, I’m exaggerating, especially when it comes to the slew of cool indie and “big indie” RPGs that have been released lately. While there’s still plenty of room for improvement, there’s at least a sense that they’ve learned the right lessons.

Narrative and gameplay form an imperfect union. Simply put – players play to win the game, not to make better dramatic choices, which spoils the narrative; but forcing those dramatic choices upon the player spoils the interactivity and gameplay. However, those competing forces can be carefully balanced to form something really cool. Maybe it cannot be the best story in the world or represent perfect gameplay, but it can be something greater than the sum of its parts. The two competing elements can enhance the flavor of their counterparts.

Filed Under: Design - Comments: Comments are off for this article

“Crap Happens” – Risk Management and Gaming

Posted by Rampant Coyote on December 18, 2014

When you play Chess, you never have to ask yourself, “If my Knight is unsuccessful in taking my opponent’s Bishop, what is my fallback plan?” Sure, you may have to come up with a plan B if your opponent chooses another (viable) move than the one you expect, but the outcome of a single move is never in doubt. There are no percentages, no tables, no dice rolls, no hit points, no chances.

When you play Chess, you never have to ask yourself, “If my Knight is unsuccessful in taking my opponent’s Bishop, what is my fallback plan?” Sure, you may have to come up with a plan B if your opponent chooses another (viable) move than the one you expect, but the outcome of a single move is never in doubt. There are no percentages, no tables, no dice rolls, no hit points, no chances.

For some players and game designers this represents a purity of gameplay – a perfection. I scratch my head at this view. I guess that’s why Chess isn’t my favorite game. Sure, it’s fine and enjoyable. I kinda prefer Go, myself, but that’s another game with no chance involved. It’s all move / countermove. Is this purity of gameplay – with perfect knowledge of the board and purely deterministic outcome for each move – an ideal? Sure. Is it *the* ideal for which all games should strive?

Not by a longshot.

I’m a simulationist at heart. While I’m cool with the occasional abstract game, I prefer games that represent something – a narrative, or a piece of reality. And one of the things about reality is that nothing ever goes as planned. Guns jam. Key players get injured. Matches get called on account of rain. Somebody forgets to carry the nine. Luke gets in a lucky shot that blows up the Death Star. An early snowfall causes ice to build up in the gaps between the tank treads, slowing the advance. Ewoks beat the Empire. The lead actor gets the flu. Brilliant tactics undermine a “perfect” strategy. A black swan event takes place. In short, crap happens.

For me, in strategy games (and RPGs), that’s part of the fun. No, I can’t say I enjoy it when I have a 90% head-shot chance and I miss. But that sort of thing is offset by the times I have only a 10% chance of a head-shot and I hit. Those are the moments I remember.

For me, I like the tough decisions when you can have a perfect understanding of the odds but still have a tough time making a choice. Do you take a guaranteed loss of 50% of your forces, or a 50% chance of a total victory with no losses but with failure meaning a total loss? While mathematically both options are equal (AFAIK, not being a mathematician), to me that’s an interesting decision. It’s the kind of thing riveting gameplay is made of.

Uncertain results means having to manage risk. It means contingencies. It means you may not want to expose your sniper for that “killer shot” because it might not pay off, and the enemy is going to be mighty pissed and see an easy target. It complicates things in a good way. So while there’s always a place for “pure” strategy, I reject the notion that it’s somehow a superior game form. In the real world, crap happens.

But even in the game world, maybe what a good strategy game needs to spice things up is a little bit of craps.

Filed Under: Strategy Games - Comments: 2 Comments to Read

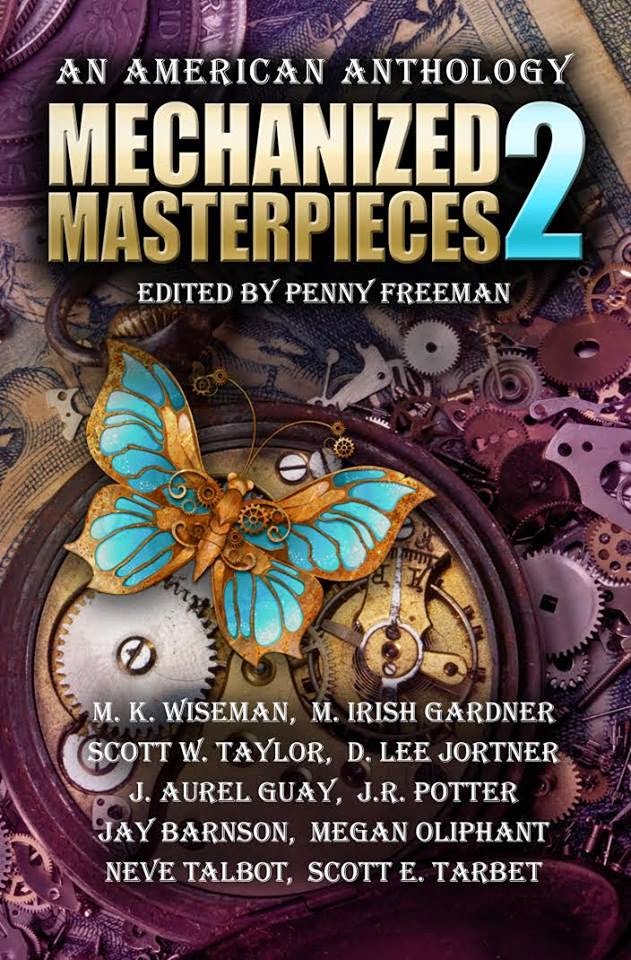

Mechanized Masterpieces 2: An American Anthology Cover Reveal

Posted by Rampant Coyote on December 17, 2014

It’s still a couple of months away, but my publisher has revealed the cover of the next Steampunk anthology, which includes the story “The Van Tassel Legacy” by yours truly:

We’re in the final stages of editing right now.

We’re in the final stages of editing right now.

I haven’t read any of the other stories, but I know some of the authors and read their previous works, and I’m excited for what they have in store. The stories are all based on classic American literature this time around, with a steampunk twist. It sounds like one of the stories is based on / inspired by Edgar Rice Burroughs’ “Barsoom” stories (Princess of Mars, etc.), which would have put this book in the “must read” category in the first place.

My story is something of a sequel to “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” by Washington Irving, taking place about fifty years after the events of the original story. I’m pretty sure that my own story is probably not anything like Irving had in mind when he wrote Sleepy Hollow, but I hope he’d be amused. As for me, well, I’m never going to read or hear the original story the same way ever again. Katrina van Tassel and Brom Bones, in particular, have been forever transformed for me.

Anyway, I thought the cover looked awesome, and wanted to share. More information forthcoming in the next few weeks!

Filed Under: Books - Comments: Read the First Comment

Guest Post: Why I Love (and Sometimes Hate) Adventure Games

Posted by Rampant Coyote on December 16, 2014

The following is a guest post by my good friend Greg Squire of Monkey Time Games. He has graciously offered to help out while I’m off in the Land of the Rising Sun. Enjoy!

The adventure game genre is filled with tons of evangelists and also tons of antagonists. And while I imagine that may be true of any game genre, it seems they are especially vocal when it comes to adventure games. Many laud the merits of the genre as an interactive storytelling medium, but many others decry that the genre barely passes the minimum qualifications to be a “game”. Many, myself included, have loved to see the resurgence of the genre in the past several years, but there are others that would like to keep the genre buried forever. In this article I hope to convey what I like and sometimes dislike about the genre.

I was first introduced to the concept of interactive stories in reading some of the old “Encyclopedia Brown” and “Choose your own Adventure” books as a kid. The idea that the story could change based upon your own choices was a powerful notion to me then. And granted these stories were fairly limited in their “interactivity”, they still opened my eyes to the possibilities. Later I was soon introduced to the world of interactive fiction (then known as “text adventures”) through a game called “Zork“. I played it for many hours on my Atari 800XL that I had purchased with my paper route money. It opened up a new world to me. I could type anything into that little prompt for the game, and it magically talked back to me. Often it would respond with “I don’t understand that” type of messages, but on occasion I’d be surprised with humorous responses. As I told the game what to do, it would comply and respond with words that advanced the story along. It was as if I was really was in that world at times, and it seemed endless. Of course that was an illusion, but it really seemed like I could do most anything that I wanted in that imaginary world. I went on and played many other Infocom and Scott Adams adventures that were popular in that day. I was hooked. The door had been opened and there was no going back.

I was first introduced to the concept of interactive stories in reading some of the old “Encyclopedia Brown” and “Choose your own Adventure” books as a kid. The idea that the story could change based upon your own choices was a powerful notion to me then. And granted these stories were fairly limited in their “interactivity”, they still opened my eyes to the possibilities. Later I was soon introduced to the world of interactive fiction (then known as “text adventures”) through a game called “Zork“. I played it for many hours on my Atari 800XL that I had purchased with my paper route money. It opened up a new world to me. I could type anything into that little prompt for the game, and it magically talked back to me. Often it would respond with “I don’t understand that” type of messages, but on occasion I’d be surprised with humorous responses. As I told the game what to do, it would comply and respond with words that advanced the story along. It was as if I was really was in that world at times, and it seemed endless. Of course that was an illusion, but it really seemed like I could do most anything that I wanted in that imaginary world. I went on and played many other Infocom and Scott Adams adventures that were popular in that day. I was hooked. The door had been opened and there was no going back.

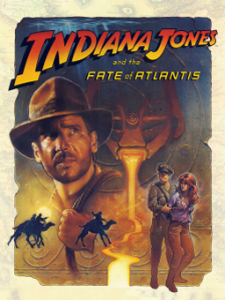

By the time the 90’s rolled around, adventure games had evolved into the familiar graphical point-n-click format that’s still in use today. I have fond memories of playing many of the Lucasarts adventures as a young adult. Monkey Island, Day of the Tentacle, Sam & Max Hit the Road, and Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis are some of my particular favorites of that era. Perhaps the nostalgia of looking back on that era is partly why I like the genre so much. Most people have fond memories of things they grew up with, but I think that’ nostalgia is only part of the equation.

By the time the 90’s rolled around, adventure games had evolved into the familiar graphical point-n-click format that’s still in use today. I have fond memories of playing many of the Lucasarts adventures as a young adult. Monkey Island, Day of the Tentacle, Sam & Max Hit the Road, and Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis are some of my particular favorites of that era. Perhaps the nostalgia of looking back on that era is partly why I like the genre so much. Most people have fond memories of things they grew up with, but I think that’ nostalgia is only part of the equation.

I feel a big part of my draw to adventure games is the exploration aspect of it. The genre encourages the player to look around their surroundings and examine the virtual environment. It’s through that exploration that items are uncovered, which are then used to solve puzzles and advance the story. It’s like a treasure hunt at its core; and who doesn’t love a good treasure hunt, right? Also it’s a mechanic that helps pull the player in and help them to feel a part of that world.

Another big aspect is story. I heard it said by Tracy Hickman and others is that the human race is wired for story. Since the dawn of man, we’ve told stories by the campfire. It’s an essential part of our being and probably why we get a lot of fulfillment from stories. It’s part of how we learn and understand the world around us. When we hear part of a story, most of us will be drawn to know how it ends. It’s part of our natural curiosity to know the ending. It’s just how we are wired, and that’s why story is such a powerful tool. Adventure games are heavily story driven, and that helps drive us to complete the game, as we want to know how the story ends. Perhaps this is the greatest reason I love the genre, as I love great stories.

The puzzle aspect of adventure games is also another draw for me. I’m a very cerebral type of person, and I tend to be a problem solver. Since my youth I’ve always liked puzzles of various types. I love the ‘ah hah’ moment you get when you figure something out on your own. That can be exhilarating, and is part of the inherent reward you get from the game. However I realize that for some, puzzles can become frustrating and can even become a deterrent. It’s a reason that some people don’t like the genre. Puzzles certainly aren’t for everyone.

Now adventure games aren’t perfect I admit, and there are some things that I and many others sometimes hate about them. Most of these boil down to bad design decisions, but they are something that has plagued the genre from time to time (mostly in the early years). The first problem is “pixel hunting”, which is when the hot spots of particular objects are made too small, thus making them hard to find. In some bad cases, the user would literally have to hunt for that one pixel (or small group of pixels) to find the needed “hotspot” to advance the game. This was a particularly bad practice in the 90’s when some designers thought it would add to the challenge and make it more fun. However it only succeeded in adding more frustration to the player.

Second is the problem of getting stuck due to overly difficult or nonsensical puzzles. This is still a problem in many adventure games today, because puzzle difficulty is relative. What might be an easy puzzle to one player, might be extremely difficult for another. Some games try to alleviate this problem by implementing a good hint system, or by making such a puzzles optional instead of mandatory. Also it’s considered bad design if the puzzle doesn’t fit naturally into the overall story and/or environment. Unfortunately many games have included nonsensical / lateral thinking puzzles, and the solution to those puzzles are so bizarre that it just frustrates the player even more. I have experienced this problem many times with adventure games, and I have had to turn to walkthroughs on the internet in order to progress through the game. In these cases of bad puzzle design, the only way to solve them is to either look up the solution in a walkthrough (cheating), or do “option exhausting”, which is where the player tries every dialog option or tries to use every object on every other object. Obviously this is very tedious to do, and most players would either cheat or quit the game. On the bright side, I haven’t been frustrated with many puzzles in adventure games these days. Not sure if that’s just because I’ve gotten better at them, or if designers have learned from the past and have made better puzzles. Hopefully the latter.

Second is the problem of getting stuck due to overly difficult or nonsensical puzzles. This is still a problem in many adventure games today, because puzzle difficulty is relative. What might be an easy puzzle to one player, might be extremely difficult for another. Some games try to alleviate this problem by implementing a good hint system, or by making such a puzzles optional instead of mandatory. Also it’s considered bad design if the puzzle doesn’t fit naturally into the overall story and/or environment. Unfortunately many games have included nonsensical / lateral thinking puzzles, and the solution to those puzzles are so bizarre that it just frustrates the player even more. I have experienced this problem many times with adventure games, and I have had to turn to walkthroughs on the internet in order to progress through the game. In these cases of bad puzzle design, the only way to solve them is to either look up the solution in a walkthrough (cheating), or do “option exhausting”, which is where the player tries every dialog option or tries to use every object on every other object. Obviously this is very tedious to do, and most players would either cheat or quit the game. On the bright side, I haven’t been frustrated with many puzzles in adventure games these days. Not sure if that’s just because I’ve gotten better at them, or if designers have learned from the past and have made better puzzles. Hopefully the latter.

Another problem I see in the adventure game genre is confusing user interfaces. Now this is an area of debate because some people love the old Lucasarts “click to construct a sentence” interface, and some love the old Sierra “verb coin” interface, where you use the secondary mouse button to change the mouse icon to the action (verb) that you want to take before clicking on an object. However I feel that both of those interfaces are overly complex, and are a hurdle to new players not familiar with the genre. I personally don’t like either of those interfaces. However it’s true that those interfaces do give you the flexibility of doing any action with any object, but I would contend that this just isn’t needed. Usually there’s only one or two actions that make sense to do on any given object. You wouldn’t TAKE a door, but you would UNLOCK or OPEN it. You wouldn’t UNLOCK a person, but you would TALK to them. You wouldn’t TALK to a banana (at least not usually), but you would TAKE it. The context is usually enough to determine the action needed. I am a big proponent of the K.I.S.S. philosophy (Keep It Simple Stupid), so I’d rather keep the player’s learning curve down with a simple interface. I much prefer a one button interface that determines the context based on the kind of object you are interacting with. Many of the Telltale and other recent adventures have used such a simple interface successfully. It can be done.

Lastly is the issue of time commitment, and depending on who you talk to, that can be an upside or a downside. I guess this one comes down to personal preference. Some people want a long drawn out experience, and feel slighted if the game doesn’t last 10+ hours. However I prefer a comparatively shorter, faster paced, but enriching experience, because my time has gotten more and more limited as I’ve gotten older. I think that’s the case with many older players, as they’ve taken on the responsibilities of work and family. I have to take my games in bite size chunks these days.

Lastly is the issue of time commitment, and depending on who you talk to, that can be an upside or a downside. I guess this one comes down to personal preference. Some people want a long drawn out experience, and feel slighted if the game doesn’t last 10+ hours. However I prefer a comparatively shorter, faster paced, but enriching experience, because my time has gotten more and more limited as I’ve gotten older. I think that’s the case with many older players, as they’ve taken on the responsibilities of work and family. I have to take my games in bite size chunks these days.

So despite the shortcomings of the genre, I still love adventure games and what they bring to the table. I think that games have the potential to be the most powerful storytelling medium, but I don’t feel that it’s there yet. I think there’s still plenty of innovation ahead. So where do we go from here? Hard to say for sure, but I’ve always imagined something like Star Trek’s holodeck technology as the holy grail for interactive storytelling. It’s hard for me to imagine anything more immersive than that. Perhaps with advancements in virtual reality and automatic story generation, we may eventually get to something akin to that. But for now we’ll have to settle with the current state of gaming. Further, there are some that still claim that adventure games are dead, or were dead but have seen a small comeback, but the reality is that they never died at all. They just morphed and evolved, like all game genres do. We don’t always call them “adventure games” anymore, but many games these days have “adventure” or heavy story elements in them. For instance, the action adventure genre, which are games like the Tomb Raider and Zelda series, are essentially adventure games with action elements thrown in. They still have strong story, exploration, and puzzle elements, but we don’t think of them in the same way as the adventure games of yesteryear, but yet they are still “adventures”. They have morphed and mutated, and for better or worse, adventure games are here to stay.

Filed Under: Adventure Games - Comments: 3 Comments to Read

Indie Game Dev Thought of the Day #1

Posted by Rampant Coyote on December 15, 2014

Dumb thought for the day:

Being a game programmer will teach you that there’s a very fine line between genius and stupidity. very fine indeed. What sounded brilliant in your head last night may prove to be absolutely unworkable, shortsighted, and stupid when you try to implement it.

Or… it might not.

Filed Under: Programming - Comments: Comments are off for this article

Making Money Making Games – Part 4 – How the indies have always done it

Posted by Rampant Coyote on December 12, 2014

So in parts 1 and part 2 of the series, I discussed how the games biz has changed over the decades. In part 3, I talked about how many different ways there were to make money from games if you are willing to step outside of the box. That’s a lot of changes and variation.

Is there anything that stays the same? Any consistency? I think so, yes. While everything else changes, a few things stay the same.

For this last article, I want to focus on the indies, and how the indies have been making it work from the get-go. Here’s the thing: The games biz started out pretty indie. Almost by definition – there were no big publishers to rule the landscape to begin with. So it began, and so it continues. Even during the 90s, which was they heyday of the giant publishers (well, mid-90s to mid-2000s, probably), indies were taking it to the streets and doing a painful but sometimes profitable end-run around the establishment.

In each era, the indies had to adopt different technologies, distribution methods, and so forth to get their games out to their potential audience. But here’s the cool part – in spite of different times, different technologies, there were some really consistent patterns.

Let’s start with one of my favorites, the creator of the original Ultima series, Richard Garriott. He made 28 role-playing games prior to his (moderate) success, Akalabeth: World of Doom, sometimes called “Ultima 0.” These games were called DND1 through DND28. They weren’t big games, and they were for technology that few had access to – the PDP 11 at his school. Akalabeth sold somewhere between 10,000 and 30,000 copies – not a stellar success even at the time, but it was enough. It made Garriott about $150k. Ultima 1 did better, selling around 20,000 copies in the first month, eventually selling around 50,000 copies at $39.95 retail. After the second game, he “went indie” and Origin went into self-publishing titles.

Many members of id Software started out making games for SoftDisk – a subscription-based, monthly software service. They made tons of games on a regular schedule with steep deadlines. They made their first three games as a company – the Commander Keen trilogy – in 3 months on a $2000 advance. Eventually, Doom would go on to sell over a million copies via “shareware,” which made the founders millions, and also paved the way for more traditional releases of Doom and other games.

The story continues. Terry Cavanaugh? He made a crapload of games before the success of VVVVVV. Popcap? Before Bejeweled, founder Jason Kapalka had been making & designing games for YEARS with TEN / Pogo. Rovio had 51 previous games, published by themselves and by third-parties. They weren’t all hits, but they weren’t all “failures” as the press likes to call them – before hitting the motherlode with Angry Birds.And then you’ve got Notch, who labored for years making dozens of games – mainly web-based titles and even one MMO – before becoming an “overnight success” with Minecraft.

Do you see something interesting here? I do. There’s almost a pattern to their success. Or a formula, if you decide that the formula is making lots of games and sticking with it. Being prolific and persistent. Of course, there’s no guarantees there, either, but if I were to suggest what indies should do to be successful, my list would look something like this:

- Start Small. Small is bigger than you think. In other words, what may seem ridiculously small in scope will actually be a much bigger project than you expect.

- Make Games – start at the beginning and make games. Small games, probably.

- Keep making games. Because it’s easy to give up after 1 or 2.

- Finish Games. Don’t just call it done when it gets hard. It’s good to learn what needs to go into a game to make it ready to sell.

- Release / Sell Games – by “sell” that includes any means available (from yesterday’s list… or not). You learn a ton unleashing your game into the public. Including the paying public. It may not be perfect feedback, but it’s something.

- Keep making games – Because the first games’ sales are almost guaranteed to disappoint.

- Play & Study Games – Don’t be in a vacuum. Learn what’s come before.

- Play Retro & Indie Games – There are a lot of brilliant ideas to be mined, here.

- Don’t stop making games. Some of the biggest successes came from the guys who were on the verge of giving up.

- Love Games – It’s apparently possible to make games and not actually like them. I don’t understand this. But if you love games, you aren’t going to be making the kind of crap that some of these companies crank out that clearly don’t love games but do love exploiting their customers.

It’s a pretty consistent path, and not just in games. Again: be prolific. Be persistent. “Make games a lot.” (Which isn’t exactly the same as “make a lot of games.”)

Filed Under: Game Development - Comments: Comments are off for this article

20 Ways to Make Money Making Games (part 3)

Posted by Rampant Coyote on December 11, 2014

A continuation from my talk at BYU. You can read part 1 here, and part 2 here.

So… throughout our relatively short history, video games have been treated by the industry as an analog to toys, books, movies, magazines (subscriptions, you know?), services, drugs (first one’s free…), widgets, television shows (advertising-supported), as a benefit of club membership, as add-ons to sell hardware, and just about everything else.

So how should one really make money and make a living making games?

By any or all of the above means, IMO.

The industry keeps changing. The way that games are made and sold (if “sold” is even the correct term… but I don’t like the term “monetized” as much) constantly changes. What seems obvious and natural today will seem weird and ridiculous twenty years from now. The next generation of gamers may look at the fact that we used to sell games individually on physical media like a cartridge or CD-ROM with a mixture of awe and horror.

Right now, if you want to make income of any kind making games, there’s two basic approaches: Indirectly, by getting paid to make a game (via employment or contract), or directly by your audience. I don’t want to talk about the former too much because it’s pretty straightforward. As someone trying to make income from games, how many ways are there?

A lot:

- Get a job – the old standby

- Contract work / Commissions – the work of the independent (not indie) studio or contractor

- Direct Sales – the classic approach. Sell the game to the end customer directly

- Portal Sales – Like direct sales, only go through a middleman, like Big Fish Games or Steam

- Get Published – Which ultimately means you sell or license rights to profit from your game to a third party. All terms are negotiable from there.

- Contests – Yes, there are game-making contests with cash and other prizes.

- Ad-based revenue (Kongregate, etc.)

- Patronage – an old idea for sponsoring the arts.

- Sponsorships – Sort of the inverse of ad-based revenue. A sponsor licenses your game to help advertise a product.

- “Freemium” – Offer the game for free, but sell virtual goods & unlocks through it.

- Licensing – You license some aspects / rights to your game to a third party. If a game or brand is successful enough, there are all kinds of IP rights that become valuable.

- Subscription – The classic (but now old-school) approach to MMOs.

- Crowd-funding – A popular, recent approach. Get paid in advance to make the game. I consider this a subset of patronage.

- Donationware – another old idea from the early shareware age. Sometimes it works.

- Bundles – It massively devalues games, but it’s a bargain for budget-conscious consumers and can get new customers to your game

- Customization – Create special, custom builds (for a price) to a particular customer to match their needs. First done (to my knowledge) with a special military version of Battlezone.

- OEM – Bundle your game with hardware as a “free” (to the customer) bonus. Similar idea to software bundle, above.

- Affiliates – An old (but still viable) concept that predates shareware. Other people sell your game, and get a cut.

- Merchandising – Make money from other products related to the IP

- Sell IP / Company – Cash In and Be done With It

These aren’t even all the possible ideas, and variations on these ideas abound. If there’s one thing the history of the games industry should teach you, it is that there is no one, true way for game-making to pay or itself.

Filed Under: Game Development - Comments: Read the First Comment