Big Indie-an vs. Little Indie-an

Posted by Rampant Coyote on September 25, 2014

“Indie” has been a purposefully inclusive title. It designated those games or game developers that worked outside the standard gatekeepers, the big game publishing industry that dominated the scene only a few years ago. It was really a catch-all to cover everybody excluded from that system. Even then, there wasn’t a great hard-and-fast rule to defining “indie.” Over the years, as the “indie revolution” has taken over, the flexible term has been stretched even further.

I always maintained that one of the purposes of the term was to reset expectations for gamers. The big-publisher industry had spent many years and an incredible amount of of money convincing people that quality could be measured in expensive production values. Of course it would – that was the one thing they could guarantee. Their games might not be innovative, or deep, or tell a good story, or really any fun… but they could definitely spend millions of dollars making it look pretty!

Calling a game “indie” helped gamers give smaller games the benefit of the doubt, and allow them to push past the big-industry filters and look at a game on its own merits, allowing it to avoid direct comparison with the $50 million budget AAA games.

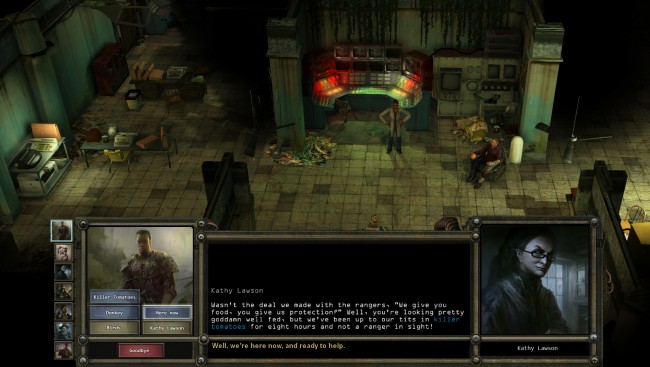

I still like the term “indie.” However, now that the indie revolution has happened, and at least in terms of number of titles released has eclipsed the mainstream biz, the inclusiveness of the term has really broadened things. You’ve got “indies” with millions of dollars of development budget (which back in the beginning of my career was AAA right there), and you’ve still got the hobbyist indie cobbling something in his bedroom. By many definitions of the term, Wasteland 2 – created with major crowdfunding effort and some in-house funding, but without any involvement by publishers – is an “indie” game.

Then you have a very, very indie (and very fun) VVVVVV by Terry Cavanagh – sort of my poster-child for awesome low-budget games:

Okay, now everything else being equal (price, etc.), I’ll admit that I’d grab Wasteland 2 before VVVVVV, and maybe not just because I’m a much bigger RPG fan than platformer fan. (But hey, as it is, I own both). But things aren’t equal. And… as much as I love “indie,” it’s a big inclusive term that by itself doesn’t allow much distinction. And I don’t know how much distinction is required. On some level, VVVVVV competes with Wasteland 2. Not very directly, probably not very quantifiably, but at least in the same way that all entertainment competes for the same disposable income. It’s not infinite.

Is that fair? I don’t know. If I was a big platformer / action game fan, I might look at Wasteland 2 and think, “Turn-based? Boring!” A quick video of VVVVVV in action, and I’d be all over that. (FWIW, I happen to know that Terry is a big RPG fan, too…)

This isn’t a new problem, of course. I remember the first big flare-up with an early (6th) IGF where Savage: The Battle for Newearth won the “open” category, where its seven-digit development budget helped grab a ton of attention if nothing else. That was a decade ago. There was a lot of cries of unfairness back then, too. Now, the problem is only exacerbated by the presence of a LOT of indies, some of whom have famous names or the ability to throw big budgets at their projects. We’ve got a lot of stratification in the “indie space.”

I don’t know if customers really care. Again, the indie revolution has won, and I think a lot of gamers are now ready to look past the surface. Graphics still have to be NICE, of course, but they don’t need to be anywhere near cutting-edge. And the screenshots still have to be compelling and stand out. That’s always true. But maybe we’ve finally broken free of the need to reset those expectations so players can take a game on its own terms, rather than comparing it to what it isn’t.

So maybe any attempt to label the the different “tiers” of indie is pointless. Maybe it serves no purpose. But for me – maybe because I’m also a developer, or just because I have the mindset of one – I like to create categories and label them. For me, I kinda see four “tiers” of indies these days, ranging from little indies to big indies. (In computer science, we have terms “Little Endian” and “Big Endian,” which describes the byte order of how numbers are represented. So I can’t think of Big / Little Indie-dom without thinking of those terms, and call it, “Little Indie-an”. Maybe I’m too easily amused to be able to offer any sort of gaming criticism…)

But even discussing budgets can get weird. You can have ten people volunteer a year of their time for a game, or pay the same ten people to do the same work. You may get the same result at the end, but it’s kind of silly to say the first game had a zero budget.

Tier 1 – Amateur / Student / Hobbyist

To me, this is the “starting tier” for indie game development, but any or all of these tiers could be bypassed completely by anybody. But there’s a whole category of people who are making games without any sort of concrete professional intent. They may harbor vague ideas of making money from their games, and even succeed in doing so, but they are not going to invest much besides their time and sweat into a project. They may just be learning to make games, or they may do frequent game jams without really focusing on a commercial venture. In spite of the lack of significant investment out-of-pocket, the effort volunteered by talented individuals can really turn the game into something amazing. Maybe not completely polished – that part gets long and boring at the end – but pretty outstanding nonetheless. Even the smallest and lowest-budget of indies can come out with great games.

Tier 2 – Small Indie

The main difference to me between this and tier 1 is professional intent. The budgets are still small, and while there may be a commercial interest involved, nobody has turned it into their full-time job yet. Or if they have, it’s not purely based on game revenue, but they are burning through other sources of income or savings.

Tier 3 – Medium Indie

This is where you have one or more full-time developers cranking on a game, but no more than four, and rarely more than a year of full-time development on a single game. This is a developer who is making it work on the indie front, but hasn’t yet made it big. Budgets for games becomes meaningful at this point, and “real” budgets for things like marketing and business development become an issue. Games at this tier have “real” budgets that start somewhere around the mid-five digits (in USD) up to hundreds of thousands. While being able to focus on making games to make a living offers a lot of advantages, burn rate becomes a real issue that the hobbyists and small indies might be able to shrug off.

Tier 4 – Big Indie

This is a growing tier these days, especially with the advent of crowdfunding possibilities to get these things started. At this level, you often have real offices, several full-time employees who may rotate between projects, and budgets starting around the mid six digits (depending on location… I guess studios out in the some countries could get along at a tenth of that) up to the low millions. (Beyond that, it’s questionable as to whether or not you really ought to be called “indie”). This is the level occupied by many AAA studios in the 1990s. Unfortunately, due to the nature of the business, they can’t survive for long without hit games – maybe not home runs, but some serious hits. They have to fight budget inflation to pay the expenses necessary to polish the game to the point where it is more likely to be a hit.

So at each tier, you have different environments under which a game is made, and possibly a different focus for the game. The hobbyist games – which may be created in spare hours by people at a AAA studio – can be a lot more about experimentation and showing off one’s talent than a polished product. The “Big Indie” studio is really just a minor league of the same game as the big publishers, with exactly the same pressures but a (hopefully) slightly more sustainable burn rate, and their titles will represent that. They may take some big risks – especially with genre – but they usually won’t try and fight the innovation war on too many fronts at once.

Does any of this matter to the customer? I honestly don’t know. I can see the difference, and I tend to judge games a little differently accordingly. But that might just be my developer bias showing. It does mean that the differentiating aspect of “indie” vs. big-budget titles (note that even major publishers may release lower-budget titles) has lost a lot of meaning. But it still means that a big chunk of the money you pay for an indie game is going directly to the developers who made it, whether to a larger team or a lone wolf.

Filed Under: Biz, Indie Evangelism - Comments: 6 Comments to Read

Dave Toulouse said,

I did the same exercise a few days ago and while I have more subdivisions it’s pretty much the same as yours.

You can check it here: http://www.over00.com/index.php/archives/2554

Simon said,

I think you nailed it with the groupings. I like to think of 2,3,4 as Garage Indie, Indie developer, and Indie Studio respectively.

Robert said,

I think I’d do the tiers differently.

One-person developer (often amateur, but not necessarily)

Small indie (2-5 people, budget under $500k and quite possibly a LOT lower than that)

Large indie (6-20 people, budget under $1 million)

Huge indie (21+ people, budget over $1 million)

Rampant Coyote said,

Yeah, those labels work well too. I like Garage Indie. That’d be me, with aspirations to being a full-time indie. (I am not sure I’d actually want to ever be a “big indie,” though I wouldn’t mind being successful enough that it could be a comfortable option).

Rampant Coyote said,

Hah – Dave. That’s the second reference I’ve seen to “Triple-I Indie.” 🙂 But yeah, this could be broken down a lot more.

I don’t personally see these as discrete stages, though. I mean, sure, most of us probably make that progression. A lot of it is because success tends to build on itself. But again, I’ve known AAA developers who tinker with indie (if their employment agreement allows) on weekends as Hobbyists, etc.

Dave Toulouse said,

Yeah I stole that “III Indie” reference from somewhere. 🙂

My definition of it though might be different than what others think about it though. That’s mostly massive money but uncertain future.

Maybe like Wasteland 2. Massive money involved, many employees, high investments and also high risks. So basically many of the high kickstarter campaigns we see. Sure you can put massive money on the game and do things out of reach to most but if it doesn’t sell after then you’re probably done.

Unstoppable would be devs who made Braid for example. Their next game could afford to not be a smashing hit that their “indie status” still wouldn’t be at risk.